Expedition Begins

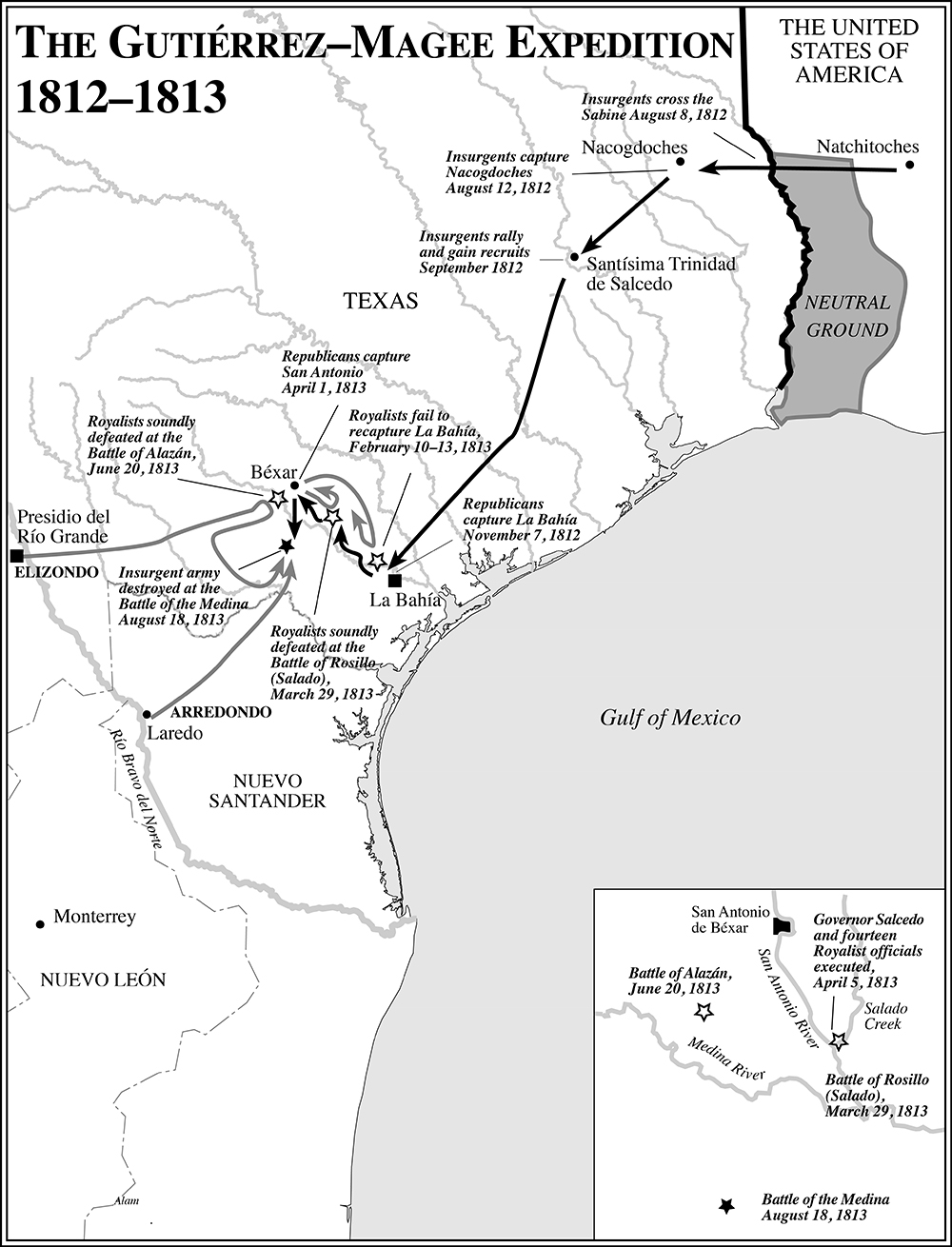

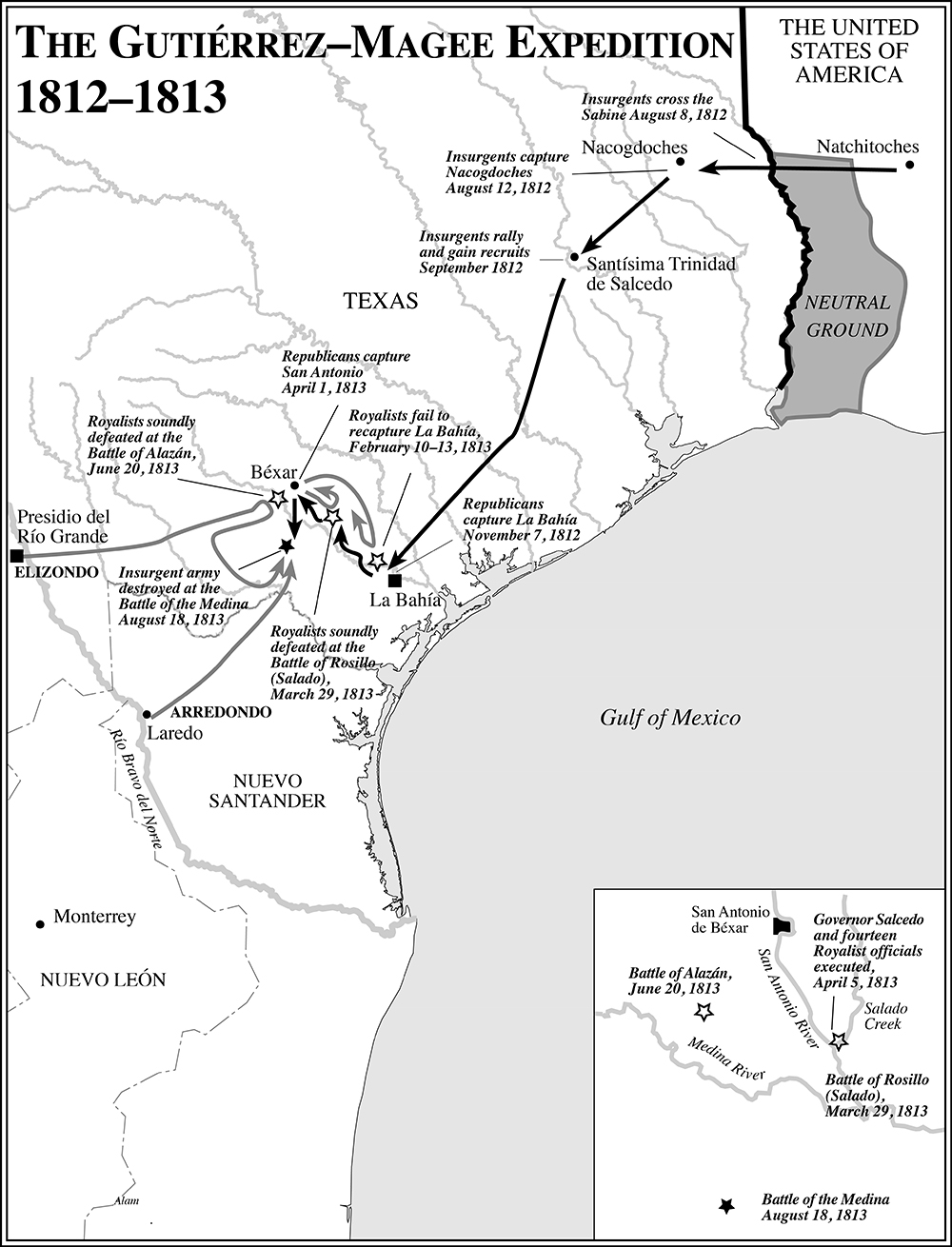

The Gutiérrez-Magee Expedition launched out of Natchitoches, Louisiana, with 130 men in the summer of 1812, arriving and capturing the town of Nacogdoches on August 12. The insurgents, led by Boston-born American Augustus Magee, American special agent William Shaler, and Mexican-born Bernardo Gutiérrez de Lara moved on, adding recruits as they went, swelling their numbers to 300.

Victory at La Bahia

The self-proclaimed Republican Army of the North captured La Bahia on November 7, fighting under a solid green flag, but Magee’s health and he was dying. Some 800 Royalist troops under governor Manuel María Salcedo besieged McGee’s army, now trapped inside the stone fort. When McGee died, Samuel Kemper assumed command and sent for more recruits to join his green-flagged army.

Spanish Counter-Attack Failed

Kemper and his men turned back a Royalist attempt to recapture La Bahia on February 10 and 13, 1813 and sent Salcedo retreating back to Béxar.

Battle of Rosillo

The Republicans followed, joined by more than 500 recruits including Spanish deserters, Tejanos, Americans, and Apache and Tonkawa Indians, brushing aside a Royalist force at the Battle of the Rosillo on March 29 before capturing the capital of Tejas on April 1, 1813. The Republicans hauled the Spanish officials, including Salcedo, out of town and shot them. Guitiérrez assumed political control and declared Texas a state and part of the Republic of Mexico.

Battle of Alazán

The Royalists under Lieutenant Colonel Ignacio Elizondo launched a counter-offensive that summer from Presidio del Rio Grande, but failed to dislodge the Republicans after a brief siege, and retreated from the Republicans at the Battle of Alazán on June 20.

Battle of the Medina

The Royalists under Elizondo, meanwhile, determined to crush this rebellion, combined with another column led by José Joaquín Arredondo coming up from Laredo. The combined Royalist force of 1,800 crushed the 1,400 Republicans at the Battle of the Medina on August 18, 1813, killing, wounding, or capturing nearly 1,300 of the rebels and sending Toledo and Shaler running back to Louisiana.

What followed was a rampage of retaliation among the population of Texas. Spanish troops targeted anyone suspected of having harbored or aided the Republic troops with swift execution. Thousands of civilians across Tejas died at the hands of Royalists troops, many more than would die in subsequent turmoil. Thousands, including Béxareños José Francisco Ruiz and José Antonio Navarro fled into the United States.

Tejas, so carefully cultivated as a Spanish borderland for more than a century, had been nearly cut back to the root by this Spanish reign of terror. Many of the founding Tejano families abandoned the region, others disintegrated as fathers, husbands, and sons fell beneath the Royalist muskets. By 1814, Spanish Texas was a mere shadow of its previous state, and would remain diminished until more people arrived to once again make its fields and rangeland productive.