Texas At The End of the Chain

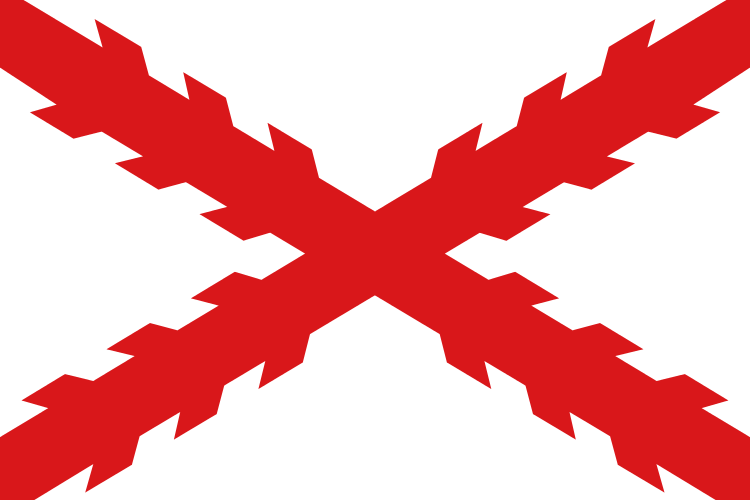

Shortly after the conquest of Mexico, the Spanish monarch established two layers of government to help manage the growing empire. The Council of the Indies dealt with New World governing issues. Trade and issued related to maximizing revenues for the crown channeled through the Casa de la Contratacíon located in the chief duty port of Seville.

In the New World, the crown established the Viceroyalty and Audiencia of New Spain. These entities were, in essence, an assistant king in Mexico aided by a privy council to provide judicial, legislative, and administrative functions in this vast area.

The Viceroyalty of New Spain developed various kingdoms, provinces, and other regional subdivision as it expanded, each headed by an appointed official and assisted by some sort of council. This created, in turn, some awkward arrangements by creating layers of often overlapping jurisdictions that often caused bureaucratic headaches for people trying to conduct official business in Mexico. A common expression, Obedezco pero no cumplo (I obey but I do not comply), expressed the attitude many of these officials had toward royal authority as they sought to navigate the maze of rules, regulations, and authorities. In the end, bribery and graft became tools for administrative efficiency.

At the local level, officials further divided most Spanish territory in the provinces into municipalities that controlled not only the settlement itself, but also the surrounding lands. Alcaldes served as chief magistrates chosen by councils called the ayuntamiento (sometimes cabildo) composed of councilmen (regidores) presided over by a chairman—el corregidor.

As the society of New Spain matured, additional layers of control and bureaucracy emerged as administrative positions sprouted among the various settlements and population centers. As a rule, the more important the post, the more likely it would be held by a European-born Spaniard—a Penisulare. Behind them would be Mexican-born Criollos.

The mass of the Mexican population remained out of this political mix while a growing number of Criollos jostled with Penisulares for political control and influence and its associated economic benefits. This reality added class as an issue to the already simmering friction of race.

On the frontera, though, people had to be more pragmatic. Issues that seemed of paramount concern in Mexico City often became muted in places like Tejas.

But who were these conspirators?